Something that I’ve seen over and over throughout the last few years in the realm of weight loss is the advice to only weigh yourself at long intervals, typically once a week, so I wanted to take the time to refute this stance a little. The idea around weighing yourself at extended intervals is to keep yourself from reacting emotionally to the data that you might have gained or lost a pound or two of water weight. For example, the average person might diet for a day, and the next day step on the scale and see that they are down a pound and decide to splurge today. Or, conversely, may see that they are up a pound, and tighten down even further, when it isn’t necessary. In both of these cases, however, the problem isn’t the data itself, but what the user is doing with it. Rather than educate the dieter about their body and teach them how to exercise self-control and stay the course, most trainers are simply telling them to only weigh themselves at long intervals to sidestep the issue. So, rather than intentionally reducing the data set, let’s spend some time understanding what’s happening in these cases and discussing how to deal with it. Then we can discuss some of the benefits of a larger data set.

First, in almost all cases, the majority short term weight changes are largely due to changes in water storage. In fact, I’ve personally noticed that I can weigh as much as two pounds different before and after urinating in the morning, which is highly illustrative of this point. There’s no use really worrying about water weight changes, unless you are competing (Powerlifting, Bodybuilding, etc.) or have symptoms of dehydration. Short of surgery, your body simply can’t gain or lose that much actual tissue very quickly.

So the major thing you should keep in mind here, regardless of how often you weight yourself, is that the single data point is not important. The single data point is simply a signal buried in some amount of noise. The thing you have to do is resolve the signal (actual weight change) from the noise (the periodic data points). You do this by using the data to plot trends. If, after tracking for a month, you notice that you are reliably two pounds lighter at the end of each week, that is a trend. The key to determining how your diet is performing is in finding and tracking the trend, resolving the signal from the noise.

And this is true regardless of how often you sample the noise by weighing yourself. However, the less data you have, the longer it takes to resolve a solid signal from the noise, and the more error prone short-term trend examinations are. To illustrate this, let’s take a simple example.

Imagine a situation where you kept your diet and exercise steady (making no changes for the full month), weighed yourself once per week, and got the following results:

| 1-Jan | 8-Jan | 15-Jan | 22-Jan | 29-Jan |

| 200 | 200 | 199 | 192 | 194 |

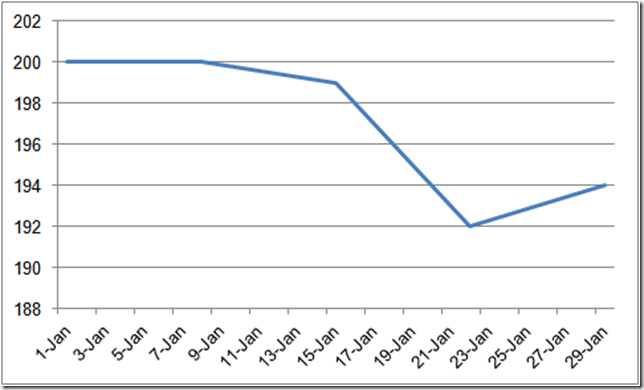

If you were to chart these results, you would get something that looked like this:

Now, if you were to make some assumptions based on this chart, they would probably look something like this:

- Week 1: Didn’t lose crap, need to tighten down

- Week 2: A little better, but still not good enough

- Week 3: HOLY CRAP, I’m losing too much, time to freak out about losing muscle, ‘starvation mode’, etc.

- Week 4: WTF? I didn’t change anything, how did I gain weight? Must be starvation mode, EEK!

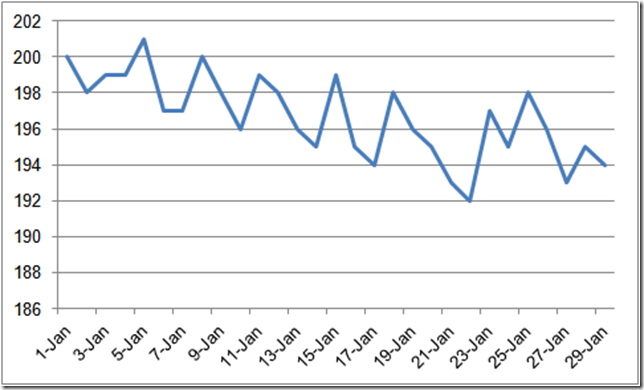

Now, let’s look at this same month through the full data set of daily weigh-ins:

| 1-Jan | 2-Jan | 3-Jan | 4-Jan | 5-Jan | 6-Jan | 7-Jan | 8-Jan | 9-Jan | 10-Jan | 11-Jan | 12-Jan | 13-Jan | 14-Jan | 15-Jan |

| 200 | 198 | 199 | 199 | 201 | 197 | 197 | 200 | 198 | 196 | 199 | 198 | 196 | 195 | 199 |

| 16-Jan | 17-Jan | 18-Jan | 19-Jan | 20-Jan | 21-Jan | 22-Jan | 23-Jan | 24-Jan | 25-Jan | 26-Jan | 27-Jan | 28-Jan | 29-Jan |

| 195 | 194 | 198 | 196 | 195 | 193 | 192 | 197 | 195 | 198 | 196 | 193 | 195 | 194 |

Charting this, this is what you get:

Very different picture, huh? Looking at this chart, it becomes immediately obvious that the general trend for the first three weeks was significant, sustained loss. In the fourth week, there was a bit of a rebound, which may be attributable to all kinds of things, but it ended with what looks like a return to the previous trend. In other words, you can easily see that no changes are really necessary.

Now obviously, both of these examples are manufactured for the sake of making my point. But the point is valid regardless: More data is not negative; it is, in fact, highly positive. More data allows you to separate the signal from the noise quicker and with a much higher level of accuracy. And the best part is, at least with weight loss, you don’t even need to be a math wiz or muck with Excel to get good trend analysis. There are two excellent apps for this express purpose: The Hacker’s Diet Online, and Libra. Both of these tools use the same algorithm, derived from the chapter (appropriately enough) on signal to noise ratio of The Hacker’s Diet. Libra is an app specifically for Android systems, while The Hacker’s Diet Online is ugly, but usable from any system with a web browser. Both are completely free.

|

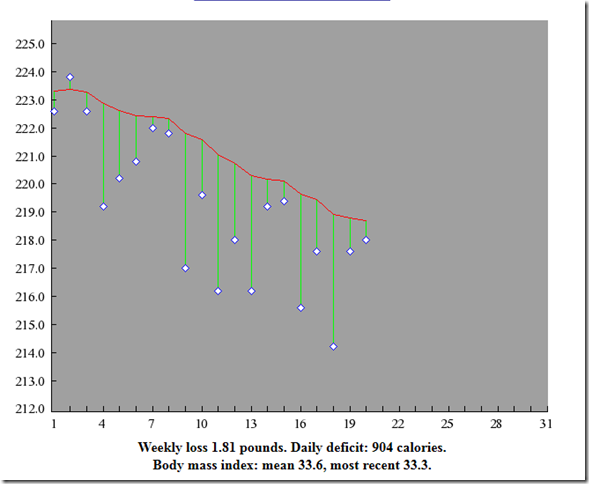

| Trending from The Hacker’s Diet Online. The ‘dots’ are my actual weigh-ins, while the red line is my weight trend-line. |

As you can see from the image above (which was taken from my real weight data) that the manufactured numbers I used previously were not too extreme. 4 lbs of variance in a day is not all that uncommon for me, and I eat a very stable diet. The less stable your diet is (and the more you drink or get dehydrated), the more variability you are likely to have.

Remember, the key to making good decisions about your weight loss data is to allow the trend to determine when you make changes, not your emotions (principally fear) or hunger.

Recent Comments